Electric Nights

from July 03 to October 29, 2020

During the nineteenth century - a period of major transformations - the night-time urban setting was profoundly altered by the advent of artificial lighting by gas and electricity. Night grew lighter as techniques and practices gradually improved. In Paris, candle lanterns were largely replaced by oil lamps, then gaslight, in the early part of the century. By the mid-nineteenth century, gaslight was beginning to face competition from electricity, first in London, then in cities in America, France and Germany. Thomas Edison's invention of the incandescent electric light-bulb, in 1879, was an important milestone in the history of lighting. From the late 1880s to the 1920s, there was huge excitement about the "Fairy Electricity" in Europe and America. Electricity represented progress, energy and vitality. Shopping arcades were the first places to be illuminated by its dazzling light, followed by city boulevards, blocks of flats, department stores, theatres and café terraces - though there had already been trials of electric arc lighting on construction sites and in harbours and railway stations, to allow work to continue after nightfall.

Cities were not modernized uniformly and different types of lighting continued to exist side by side, in competition with each other, until the eve of the First World War. This resulted in a composite night-time setting. Streets and outlying neighbourhoods where the lighting was scarce and patchy remained dark or dimly lit, while other neighbourhoods were amply or even abundantly provided with street lights at regular intervals. Each type of light was associated with a particular ambience - gaslight was seen as warm and soft, while electric light was colder - creating "a dreamscape in which the flickering yellow of gaslight is married with the lunar frigidity of the electrical spark." (Walter Benjamin) The differing ambiences created by artificial light altered the way the visual and sensory experience of being in a city at night. Artists took a keen interest in the debates and questionings that accompanied this revolutionary change in the setting, sometimes expressing scepticism or enthusiasm.

In a world increasingly dominated by modernity, the exhibition endeavours to show how this many-faceted transformation inspired the most innovative artists - those whose explorations centred on the issue of light.

After the major period of change that culminated in the First World War, electricity finally prevailed, and the figure of the lamplighter was consigned to the past.

Cities were not modernized uniformly and different types of lighting continued to exist side by side, in competition with each other, until the eve of the First World War. This resulted in a composite night-time setting. Streets and outlying neighbourhoods where the lighting was scarce and patchy remained dark or dimly lit, while other neighbourhoods were amply or even abundantly provided with street lights at regular intervals. Each type of light was associated with a particular ambience - gaslight was seen as warm and soft, while electric light was colder - creating "a dreamscape in which the flickering yellow of gaslight is married with the lunar frigidity of the electrical spark." (Walter Benjamin) The differing ambiences created by artificial light altered the way the visual and sensory experience of being in a city at night. Artists took a keen interest in the debates and questionings that accompanied this revolutionary change in the setting, sometimes expressing scepticism or enthusiasm.

In a world increasingly dominated by modernity, the exhibition endeavours to show how this many-faceted transformation inspired the most innovative artists - those whose explorations centred on the issue of light.

After the major period of change that culminated in the First World War, electricity finally prevailed, and the figure of the lamplighter was consigned to the past.

1 - The street lamp - a new feature of the urban setting

Street lamps began to appear in the urban setting in the early nineteenth century. Their arrival was linked with efforts to modernize city streets and the introduction of pavements. Until then, streets had been lit by first candle lanterns, then oil lamps, attached to the facades of houses, hanging from gallows in open spaces or suspended over the middle of the street by a cord running from one side of the street to the other.

The advent of gaslight brought the first street lamps on columns, fed by underground conduits and interconnected with each other and with gasworks. These were often sited, along with their gasometers, on the outskirts of towns and cities. Street lamps began to be produced in great numbers and variety. Their shapes and how ornate they were depended on where and how they were to be used. The large-scale public works conducted by Baron Haussmann in Paris under the Second Empire created wide boulevards, broad pavements and new squares to make it easier for people to stroll and get around the city. All these new spaces had to be lit. Between 1853 and 1890, the number of gas-jets in Paris rose from 12,400 to 51,500.

Although lighting was their chief purpose, street lamps also played an important part in daytime. Like the many trees planted at the same time, they helped structure and beautify public spaces.

Not surprisingly, this new feature of the landscape appears in the works of the group of artists most alert to all expressions of modernity - the Impressionists. However, street lamps initially appeared in depictions of daytime scenes. Their streamlined shape created a line of tension and became the axis around which the composition was organized.

The deliberately orchestrated pre-eminence of the street lamp seems to transpose its role in the street into visual form. In art, as in the urban setting, its tall silhouette helps structure the space.

The advent of gaslight brought the first street lamps on columns, fed by underground conduits and interconnected with each other and with gasworks. These were often sited, along with their gasometers, on the outskirts of towns and cities. Street lamps began to be produced in great numbers and variety. Their shapes and how ornate they were depended on where and how they were to be used. The large-scale public works conducted by Baron Haussmann in Paris under the Second Empire created wide boulevards, broad pavements and new squares to make it easier for people to stroll and get around the city. All these new spaces had to be lit. Between 1853 and 1890, the number of gas-jets in Paris rose from 12,400 to 51,500.

Although lighting was their chief purpose, street lamps also played an important part in daytime. Like the many trees planted at the same time, they helped structure and beautify public spaces.

Not surprisingly, this new feature of the landscape appears in the works of the group of artists most alert to all expressions of modernity - the Impressionists. However, street lamps initially appeared in depictions of daytime scenes. Their streamlined shape created a line of tension and became the axis around which the composition was organized.

The deliberately orchestrated pre-eminence of the street lamp seems to transpose its role in the street into visual form. In art, as in the urban setting, its tall silhouette helps structure the space.

Gustave CAILLEBOTTE (1848-1894), Rue de Paris, temps de pluie, 1877, oil on canvas, 54 x 65 cm. . © Christian Baraja / Bridgeman Images

2 - Charles Marville and the street lamps of Paris

Charles Marville (1813-1879) was official photographer of the City of Paris from the early 1860s until his death. He took these photographs during the Second Empire and the Third Republic. He must have been commissioned to take them - in several stages - by the Parisian authorities presided over by Haussmann - specifically, by the Promenades and Plantations department and then the Public Works department, both of which were directed by Adolphe Alphand, but the precise circumstances surrounding the commission are still not known. Unfortunately, the archives of the Hôtel de Ville were destroyed when the main buildings occupied by the Paris authorities were burned down during the Paris Commune, in May 1871. However, more recent sources indicate that Marville took at least 90 photographs recording the industrial and artistic heritage of the French capital, which were shown all over the world at international exhibitions and World's Fairs, either as framed prints or in albums. After Marville's death, the photographer Louis Emile Durandelle (1839-1917) added several photographs to this impressive series.

In addition to their architectural interest, these compositions are stylistically impressive. They contain no moving human figures, because of the length of time needed to take the photographs. These portrait-like depictions of street lamps – generally referred to as candélabres (candelabras) or becs de gaz (gas-jets) in the nineteenth century – detail the array of elegant designs that graced public places. From plain unadorned columns set on a base and topped by a square lantern, to imposing pedestals surmounted by bouquets of two, three or five branches, each bearing a graceful round lantern, all this lighting apparatus was manufactured and maintained by firms that had concessions to look after the street furniture of Paris.

In addition to their architectural interest, these compositions are stylistically impressive. They contain no moving human figures, because of the length of time needed to take the photographs. These portrait-like depictions of street lamps – generally referred to as candélabres (candelabras) or becs de gaz (gas-jets) in the nineteenth century – detail the array of elegant designs that graced public places. From plain unadorned columns set on a base and topped by a square lantern, to imposing pedestals surmounted by bouquets of two, three or five branches, each bearing a graceful round lantern, all this lighting apparatus was manufactured and maintained by firms that had concessions to look after the street furniture of Paris.

Charles Marville, Lampadaire devant l’hôtel Rothschild, à l’angle de la rue de Rivoli et de la rue Saint Florentin, Paris, , vers 1865, , 35.8 x 25.6 cm. . © Charles Marville/BHdV/Roger-Viollet

3 - The "republic" of the street lamps

As curious observers of their surroundings, artists endeavoured to reproduce the varied shapes of this new feature of the urban setting - not only, like Gustave Caillebotte, in chic or newly laid-out city neighbourhoods, but also, like Henri Le Sidaner in Petit-Fort-Philippe, and the Swedish artist Anders Zorn at Saint Ives, in Cornwall, in provincial locations. In these pictures, a single street lamp in a public place such as a square, a bridge or a jetty is carefully depicted, but the painter's chief concern is to show how this solitary presence affects the atmosphere of the place.

In Le Sidaner's and Zorn's pictures, modernity is timidly introduced in a small town or village that retains the nostalgic charm of the past. However, depictions of the street lamp of the poor - plain in design and weakened by age, convey something quite different. They indicate a place on the outskirts of a town or city or in a working-class neighbourhood. Albert Marquet's Le Réverbère à Arcueil (The Lamp Post, Arcueil) does not signify conquering modernity, but the destitution of a corner of the Paris suburbs left out of all the grand schemes.

Improvements to artificial lighting and the use of electricity sparked a new generation of street lighting, as seen in Camille Pissarro's painting of the tall shape of a recently-installed voltaic arc light in Le Havre, done from the window of a hotel on the main quay. The light emitted by this type of light was so powerful it was blinding, so the light-sources had to be positioned high up. These new street lights came in a variety of forms and were mainly used in places where people were engaged in work, at junctions and on boulevards. They appear in the series of views of Paris painted by Pissarro in the 1890s - he was one of the few Impressionists to show them in their lit state (in a night-time view of the Boulevard Montmartre).

Presently, the city began to light up as night fell.

In Le Sidaner's and Zorn's pictures, modernity is timidly introduced in a small town or village that retains the nostalgic charm of the past. However, depictions of the street lamp of the poor - plain in design and weakened by age, convey something quite different. They indicate a place on the outskirts of a town or city or in a working-class neighbourhood. Albert Marquet's Le Réverbère à Arcueil (The Lamp Post, Arcueil) does not signify conquering modernity, but the destitution of a corner of the Paris suburbs left out of all the grand schemes.

Improvements to artificial lighting and the use of electricity sparked a new generation of street lighting, as seen in Camille Pissarro's painting of the tall shape of a recently-installed voltaic arc light in Le Havre, done from the window of a hotel on the main quay. The light emitted by this type of light was so powerful it was blinding, so the light-sources had to be positioned high up. These new street lights came in a variety of forms and were mainly used in places where people were engaged in work, at junctions and on boulevards. They appear in the series of views of Paris painted by Pissarro in the 1890s - he was one of the few Impressionists to show them in their lit state (in a night-time view of the Boulevard Montmartre).

Presently, the city began to light up as night fell.

Camille PISSARRO (1831-1903), L'Anse des Pilotes et le brise-lames est, Le Havre, après-midi, temps ensoleillé (détail), 1903, oil on canvas, 54.5 x 65.3 cm. . © 2013 MuMa Le Havre / David Fogel

4 - Paris, the "City of Light"

The first trials of electricity as a source of artificial light were actually conducted in public places, like the experiments carried out in the Place de la Concorde in 1843. They were thrilling events that caused a sensation and were much talked about. In 1855, the Gazette de France reported of recent trials that "the light-source, which lit up a vast area, was so powerfully bright that the ladies who had been invited to witness the experiment opened their parasols, not to congratulate the inventors, but to protect themselves against the fires of this mysterious new sun." Parisians divided between believers in progress and sceptics. The press echoed their reactions and questionings; caricaturists mocked their sentiments of enthusiasm, nervousness or hostility.

The international exhibitions and World's Fairs held in Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century helped engineer the success of technological advances, especially in the area of lighting. The American Thomas Edison, who invented the incandescent electric light-bulb, was the star of the International Exposition of Electricity held in Paris in 1881, which was visited by almost 900,000 people. Already, at the 1878 World's Fair, the Avenue de l’Opéra had been lit with a large number of Jablochkoff's globular electric arc lamps on an experimental basis. In 1889, the imposing silhouette of the Eiffel Tower, built to mark the centenary of the French Revolution, was lit by a combination of gaslight - to emphasize the shapes of the structure - and electricity for the highly powerful beacon placed at the top, which could be seen from a long way away.

At the 1900 World's Fair eleven years later, the "Fairy Electricity" reigned supreme. This time, the Eiffel Tower was decorated with thousands of electric light bulbs, surmounted by a rotating beacon whose beam lit up the entire city of Paris. Alongside it was a light-fountain of 12,000 lamps, a Palace of Electricity and Optics, and a Palace of Illusions. The first line of the Metro to open speeded up access to the site. The recently invented Cinematograph was all the rage, and the dancer Loïe Fuller performed a dance whose choreography made great play with light, in homage to the magical new form of energy. The Fair was a phenomenal success, attracting over 50 million visitors.

The international exhibitions and World's Fairs held in Paris in the second half of the nineteenth century helped engineer the success of technological advances, especially in the area of lighting. The American Thomas Edison, who invented the incandescent electric light-bulb, was the star of the International Exposition of Electricity held in Paris in 1881, which was visited by almost 900,000 people. Already, at the 1878 World's Fair, the Avenue de l’Opéra had been lit with a large number of Jablochkoff's globular electric arc lamps on an experimental basis. In 1889, the imposing silhouette of the Eiffel Tower, built to mark the centenary of the French Revolution, was lit by a combination of gaslight - to emphasize the shapes of the structure - and electricity for the highly powerful beacon placed at the top, which could be seen from a long way away.

At the 1900 World's Fair eleven years later, the "Fairy Electricity" reigned supreme. This time, the Eiffel Tower was decorated with thousands of electric light bulbs, surmounted by a rotating beacon whose beam lit up the entire city of Paris. Alongside it was a light-fountain of 12,000 lamps, a Palace of Electricity and Optics, and a Palace of Illusions. The first line of the Metro to open speeded up access to the site. The recently invented Cinematograph was all the rage, and the dancer Loïe Fuller performed a dance whose choreography made great play with light, in homage to the magical new form of energy. The Fair was a phenomenal success, attracting over 50 million visitors.

Henri Le Sidaner, Place de la Concorde, 1909, oil on canvas, 101 x 151 cm. . © Bridgeman Images

5 - New denizens of the night

In the nineteenth century, the changes to the urban setting brought about by street lighting profoundly altered the way people lived at night, both by making it possible to carry on with laborious tasks such as construction or supplying and maintaining cities and by fostering the development of leisure activities.

During the July Monarchy of 1830-1848, gaslight facilitated the emergence of "nightlife" by making it possible to continue leisure activities (by definition, a practice only engaged in by idlers) later into the evening. More widespread artificial lighting by gas and electricity meant that boulevards, arcades and the vicinities of department stores and entertainment venues were brightly lit, and more people were out and about after nightfall.

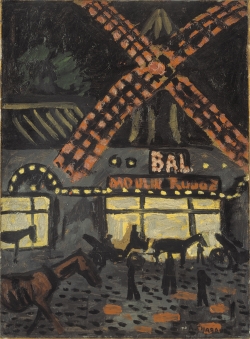

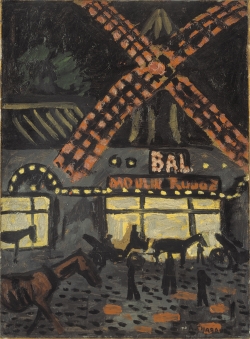

Cafés opened onto the street, encouraging people to socialize in the evening, and lit-up shop windows beckoned them to consume. The Moulin Rouge, which opened on 6 October 1889, attracted large audiences, and the coloured light-bulbs that adorned the sails of the windmill shone out in the night, promising "electric" delights to those who ventured inside.

As light invaded the streets and transformed the world of entertainment, it provided artists with new subjects. Café terraces (as in Pierre Bonnard's pictures) and the entrances of entertainment venues became miniature stages, with pavements as the front row of the audience.

In Jules Chéret's and Félix Vallotton's pictures, graphic silhouettes draw attention to the backlighting effect produced by looking directly at the light from the shop windows or street lamps. Electric street lighting also cast a powerful light on the new denizens of the night, turning them ghostly white, as in Piet van der Hem's and Hermen Anglada-Camarasa's paintings. Away from the squares and boulevards, more dimly-lit streets retained some of their mystery and ambiguity for passers-by. Like a moth, Léon Kaufman's nocturnal beauty seems to be attracted to the light, yet her gaze is concealed by the shadow of her eccentric hat.

During the July Monarchy of 1830-1848, gaslight facilitated the emergence of "nightlife" by making it possible to continue leisure activities (by definition, a practice only engaged in by idlers) later into the evening. More widespread artificial lighting by gas and electricity meant that boulevards, arcades and the vicinities of department stores and entertainment venues were brightly lit, and more people were out and about after nightfall.

Cafés opened onto the street, encouraging people to socialize in the evening, and lit-up shop windows beckoned them to consume. The Moulin Rouge, which opened on 6 October 1889, attracted large audiences, and the coloured light-bulbs that adorned the sails of the windmill shone out in the night, promising "electric" delights to those who ventured inside.

As light invaded the streets and transformed the world of entertainment, it provided artists with new subjects. Café terraces (as in Pierre Bonnard's pictures) and the entrances of entertainment venues became miniature stages, with pavements as the front row of the audience.

In Jules Chéret's and Félix Vallotton's pictures, graphic silhouettes draw attention to the backlighting effect produced by looking directly at the light from the shop windows or street lamps. Electric street lighting also cast a powerful light on the new denizens of the night, turning them ghostly white, as in Piet van der Hem's and Hermen Anglada-Camarasa's paintings. Away from the squares and boulevards, more dimly-lit streets retained some of their mystery and ambiguity for passers-by. Like a moth, Léon Kaufman's nocturnal beauty seems to be attracted to the light, yet her gaze is concealed by the shadow of her eccentric hat.

, Le Moulin Rouge, la nuit, vers 1907, oil on wood, 82 x 60 cm. . © Studio Monique Bernaz

6 - The dark side of the city

Street lighting had always been used as a means of maintaining order in urban areas - which was why lanterns were often the first things to be targeted by Parisian revolutionaries and insurrectionists until the mid-nineteenth century. However, considerations of public safety came up against economic rationales, which hindered the spread of street lighting throughout the city. For the private firms that installed gas street lighting, it was more profitable to equip wealthy neighbourhoods where there would be plenty of subscribers than poor districts. Considerations of profitability continued to prevail after the gas companies were merged into the Compagnie parisienne de l’éclairage et du chauffage par le gaz.

As a result, for a long time, the night-time urban setting was a hotch-potch. Darkness was still part of the experience of being in the city at night, but it was concentrated in patches, which might be found next to better-lit or even brightly-lit areas. In addition, darkness returned when, to save money, one in two street lamps was turned off at certain times of night, at certain points in the lunar calendar. The varying locations and intensity of street lighting from street to street and neighbourhood to neighbourhood, created dotted lines made up of successive haloes of light.

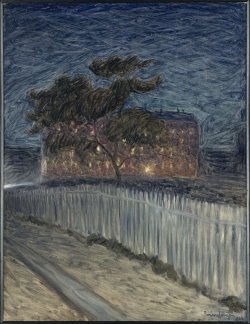

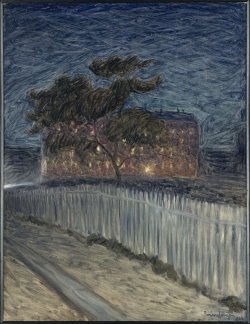

It was in the suburbs, on the outskirts of the city and sometimes even in one of the remaining narrow streets of old Paris, such as the Rue de la Vieille-Lanterne, where the poet Gérard de Nerval committed suicide in 1859, that this semi-darkness intermittently dotted with light was to be found (as shown in Eugène Jansson's Proletarian Housing). The slums depicted by the politically committed artist Théophile Steinlen in Le Bouge (The Dive) were darker still. In Steinlen's oeuvre, the social and political dimension of these depictions of underprivileged neighbourhoods is summed up by the question two children ask their father on the way back from 14 July celebrations: "Daddy, why was the Bastille taken?"

The halo surrounding a lone street lamp became a frequent subject in depictions of the night-time urban setting. In Toulouse-Lautrec's highly graphic illustration, it takes the form of a double beam piercing the darkness. The street lamp is so closely associated with the idea of the light it emits that Medardo Rosso's sculpture manages to suggest the light that falls from the lantern and illuminates the entwined pair of lovers.

As a result, for a long time, the night-time urban setting was a hotch-potch. Darkness was still part of the experience of being in the city at night, but it was concentrated in patches, which might be found next to better-lit or even brightly-lit areas. In addition, darkness returned when, to save money, one in two street lamps was turned off at certain times of night, at certain points in the lunar calendar. The varying locations and intensity of street lighting from street to street and neighbourhood to neighbourhood, created dotted lines made up of successive haloes of light.

It was in the suburbs, on the outskirts of the city and sometimes even in one of the remaining narrow streets of old Paris, such as the Rue de la Vieille-Lanterne, where the poet Gérard de Nerval committed suicide in 1859, that this semi-darkness intermittently dotted with light was to be found (as shown in Eugène Jansson's Proletarian Housing). The slums depicted by the politically committed artist Théophile Steinlen in Le Bouge (The Dive) were darker still. In Steinlen's oeuvre, the social and political dimension of these depictions of underprivileged neighbourhoods is summed up by the question two children ask their father on the way back from 14 July celebrations: "Daddy, why was the Bastille taken?"

The halo surrounding a lone street lamp became a frequent subject in depictions of the night-time urban setting. In Toulouse-Lautrec's highly graphic illustration, it takes the form of a double beam piercing the darkness. The street lamp is so closely associated with the idea of the light it emits that Medardo Rosso's sculpture manages to suggest the light that falls from the lantern and illuminates the entwined pair of lovers.

Eugène JANSSON (1862-1915), Logement prolétaire, 1898, oil on canvas, 117 x 89.5 cm. . © RMN-Grand-Palais (musée d’Orsay) / Hervé Lewandowski

7 - Night-time lighting in Le Havre

Throughout the nineteenth century, the port and city of Le Havre played a pioneering role in lighting of public places. In 1801, Le Havre was the scene of experiments with gaslight, when Philippe Lebon (1767-1804) conducted semi-public trials of his thermolamp, showing that a hydrogen and carbon-based gas could be used for lighting. In 1863, the lighthouses at La Hève became the first in the world to be lit by electricity, prompting artists and writers to explore the variations in light produced by artificial lighting.

In 1872-1873, after returning from London, where he may have met James McNeill Whistler, Claude Monet came to Le Havre. In Le Port du Havre, effet de nuit (The Port of Le Havre, Night Effect), he embraced the new pictorial subject offered by the gas-lamps the civil engineering department had begun to install in the port in 1869.

As of 1881, the outer harbour was lit by 34 electric lights, enabling ships to take advantage of night-time tides. In the late 1880s, Siebe Ten Cate painted the semi-darkness on the main quay, pierced only by the pale haloes of the electric street lamps and the bow lights of boats. From 1891 onwards, a new lighting system was introduced for the outer harbour, featuring Pilsen regulating mechanisms and imposing electric pylons 26.5 metres tall. A few months later, the Le Havre painter and engraver Gaston Prunier illustrated the city's new night-time ambience with a series of etchings, published in 1892 in the book Le Havre, effets de soir et de nuit. In the same period, Gabriel Loppé took a rare night-time photograph on the main quay, showing the distinctive conical beams of white light cast by the pylons.

Claude Monet's picture, Le Port du Havre, effet de nuit is scheduled to feature in several exhibitions during 2020. It will be on display at MuMa from the 3rd of July to the end of August 2020.

In 1872-1873, after returning from London, where he may have met James McNeill Whistler, Claude Monet came to Le Havre. In Le Port du Havre, effet de nuit (The Port of Le Havre, Night Effect), he embraced the new pictorial subject offered by the gas-lamps the civil engineering department had begun to install in the port in 1869.

As of 1881, the outer harbour was lit by 34 electric lights, enabling ships to take advantage of night-time tides. In the late 1880s, Siebe Ten Cate painted the semi-darkness on the main quay, pierced only by the pale haloes of the electric street lamps and the bow lights of boats. From 1891 onwards, a new lighting system was introduced for the outer harbour, featuring Pilsen regulating mechanisms and imposing electric pylons 26.5 metres tall. A few months later, the Le Havre painter and engraver Gaston Prunier illustrated the city's new night-time ambience with a series of etchings, published in 1892 in the book Le Havre, effets de soir et de nuit. In the same period, Gabriel Loppé took a rare night-time photograph on the main quay, showing the distinctive conical beams of white light cast by the pylons.

Claude Monet's picture, Le Port du Havre, effet de nuit is scheduled to feature in several exhibitions during 2020. It will be on display at MuMa from the 3rd of July to the end of August 2020.

Claude MONET (1840-1926), Le Port du Havre, effet de nuit, 1873, oil on canvas, 60 x 81 cm. Private collection. © DR

8 - New visual experiences

The first Impressionist exhibition, which was held in the former Paris studio of the photographer Nadar and opened on 15 April 1874. It was also the first evening exhibition, making use of gaslight, then a brand-new innovation. Yet the Impressionists do not seem to have taken much interest in artificial lighting or night-time street life.

At the time of the exhibition, Monet had just painted a highly experimental nocturne in Le Havre, but the picture remained an isolated experiment until 1901, when he returned to the subject - highly atypical in his career - for three sketches that he did not finish. The Impressionists chiefly painted daytime light, and those that did depict artificial light chose to focus on interiors, be they private (in the case of Mary Cassatt) or public, like the theatre auditoriums or backstage scenes featured in paintings by Degas and others. Why were they so reluctant to paint landscapes by night? Did the new light and the way it affected things seem too harsh and unsubtle to them? Was the genre itself perhaps too closely associated with a Romantic approach to landscape (the countryside by moonlight)?

The neo-Impressionists did not share their reservations. Seurat, Anquetin, Angrand, Luce and others invented new sets of rules based on the theory of simultaneous contrast developed by the chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul, according to which colour becomes brighter, more vibrant and more luminous when it is made up of juxtaposed dots of bright contrasting colours, at the very moment when Van Gogh was painting his Starry Night Over the Rhône (1888). These painters compensated for the night-time absence of colour by applying unmixed paints in small strokes, using associations and contrasts such as orange and yellow with blue and purple) to convey the shimmering quality of light and its reflections in the half-light at the close of day.

They generally preferred dusk to pitch darkness, as can be seen in Maximilien Luce's pictures, because it allowed them suggest shapes before they faded and then disappeared as the city was engulfed in darkness.

On the cusp of the twentieth century, the neo-Impressionists' explorations paved the way for the Futurists' chromatic abstractions.

At the time of the exhibition, Monet had just painted a highly experimental nocturne in Le Havre, but the picture remained an isolated experiment until 1901, when he returned to the subject - highly atypical in his career - for three sketches that he did not finish. The Impressionists chiefly painted daytime light, and those that did depict artificial light chose to focus on interiors, be they private (in the case of Mary Cassatt) or public, like the theatre auditoriums or backstage scenes featured in paintings by Degas and others. Why were they so reluctant to paint landscapes by night? Did the new light and the way it affected things seem too harsh and unsubtle to them? Was the genre itself perhaps too closely associated with a Romantic approach to landscape (the countryside by moonlight)?

The neo-Impressionists did not share their reservations. Seurat, Anquetin, Angrand, Luce and others invented new sets of rules based on the theory of simultaneous contrast developed by the chemist Michel-Eugène Chevreul, according to which colour becomes brighter, more vibrant and more luminous when it is made up of juxtaposed dots of bright contrasting colours, at the very moment when Van Gogh was painting his Starry Night Over the Rhône (1888). These painters compensated for the night-time absence of colour by applying unmixed paints in small strokes, using associations and contrasts such as orange and yellow with blue and purple) to convey the shimmering quality of light and its reflections in the half-light at the close of day.

They generally preferred dusk to pitch darkness, as can be seen in Maximilien Luce's pictures, because it allowed them suggest shapes before they faded and then disappeared as the city was engulfed in darkness.

On the cusp of the twentieth century, the neo-Impressionists' explorations paved the way for the Futurists' chromatic abstractions.

Louis Hayet, La Parade, 1888, oil on board, 19.2 x 27.2 cm. . © Studio Monique Bernaz

9 - The colours of night

Despite the major changes taking place in towns and cities, night continued to be associated with varying degrees of darkness. Painters like Józef Pankiewicz and Giovanni Boldini and engravers like Théophile Steinlen successfully conveyed pitch darkness or subtle variations in degrees of shadow, but the light-show offered by towns and cities in the second half of the nineteenth century also offered a whole gamut of tones and ambiences, depending on the source of energy.

Unlike electricity, gaz burned as a flame, and so remained symbolically connected with the idea of a hearth. However, although it was shielded by its glass lantern, the flame was not completely sheltered from wind and draughts. The image of the guttering flame is often found in the poetry of the time. Baudelaire alludes to "la clarté rouge d’un réverbère / dont le vent bat la flamme et tourmente le verre" ("a street lamp's red glare / its flame battered and its glass tormented by the wind", Le Vin des chiffonniers, 1854). Conversely, electric light was steady.

The two types of lighting were also distinguished by temperature. Electric light seemed colder and whiter than gaslight - blinding, even, in the case of voltaic arc lights. Baron Haussmann himself wroted that it had "un ton blafard, lunaire…déplaisant" ("an unpleasant . . . wan, lunar hue"), while others waxed lyrical about the polar beauty of the electrical fairyland.

When Carl Salzmann immortalized Berlin's first electric street lighting in 1884, he conveyed, as did Darío de Regoyos in Spain (in Luz electrica), the powerful brightness of electric light, which drains whites of colour, "turns [them] imperceptibly blue" and accentuates the shadows it casts. By contrast, gaslight seems warmer. The writer Emile Magne felt that gaslight allowed the street to retain "its intimacy, its blurred outlines, its chiaroscuros".

The fact that the two types of lighting co-existed until the First World War prolonged this varied spectacle. Presently, colour was added to the mix. As of 1868, Morris Columns began to make their appearance. Their backlit posters brightened the streets with splashes of colour at regular intervals, as shown in Gabriel Biessy's Colonne Morris, nocturne parisien (Morris Column, Parisian Nocturne, circa 1900). In 1910, the French chemist Georges Claude added the finishing touch to illuminated advertising by inventing the neon lighting tube. Sales of neon lights rapidly took off, completing the transformation of night-time in cities.

Unlike electricity, gaz burned as a flame, and so remained symbolically connected with the idea of a hearth. However, although it was shielded by its glass lantern, the flame was not completely sheltered from wind and draughts. The image of the guttering flame is often found in the poetry of the time. Baudelaire alludes to "la clarté rouge d’un réverbère / dont le vent bat la flamme et tourmente le verre" ("a street lamp's red glare / its flame battered and its glass tormented by the wind", Le Vin des chiffonniers, 1854). Conversely, electric light was steady.

The two types of lighting were also distinguished by temperature. Electric light seemed colder and whiter than gaslight - blinding, even, in the case of voltaic arc lights. Baron Haussmann himself wroted that it had "un ton blafard, lunaire…déplaisant" ("an unpleasant . . . wan, lunar hue"), while others waxed lyrical about the polar beauty of the electrical fairyland.

When Carl Salzmann immortalized Berlin's first electric street lighting in 1884, he conveyed, as did Darío de Regoyos in Spain (in Luz electrica), the powerful brightness of electric light, which drains whites of colour, "turns [them] imperceptibly blue" and accentuates the shadows it casts. By contrast, gaslight seems warmer. The writer Emile Magne felt that gaslight allowed the street to retain "its intimacy, its blurred outlines, its chiaroscuros".

The fact that the two types of lighting co-existed until the First World War prolonged this varied spectacle. Presently, colour was added to the mix. As of 1868, Morris Columns began to make their appearance. Their backlit posters brightened the streets with splashes of colour at regular intervals, as shown in Gabriel Biessy's Colonne Morris, nocturne parisien (Morris Column, Parisian Nocturne, circa 1900). In 1910, the French chemist Georges Claude added the finishing touch to illuminated advertising by inventing the neon lighting tube. Sales of neon lights rapidly took off, completing the transformation of night-time in cities.

Dario de Regoyos, Luz electrica, 1901, oil on canvas, 73 x 59.5 cm. . © DR

10 - Nocturnal reveries

In 1871, the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), who was living in London, began painting a series of views of the Thames at night, which he entitled first Moonlights then Nocturnes - a term borrowed from music. Painted in the studio after long phases of observation from life, these pictures are strikingly economical, with their limited palette of colours and simplified shapes. Working from memory enabled Whistler to detach himself from what he had seen and produce a sublimated image of a place and a moment. City lights play a discreet but essential part. They are often set in the distance, marking the boundaries of the composition, indicating the presence of human beings and introducing a few lighter notes in pictures that are otherwise virtually monochromatic. The subtle harmonies of tones, evanescent shapes and diffuse impression of time standing still create a poetic, mysterious atmosphere.

From the moment Whistler's Nocturnes were shown in London, Paris and Brussels, they were hugely successful. A whole generation of artists including Whistler's friend and assistant Walter Greaves (1846-1930), Charles Lacoste (1870-1959), and the Belgians Alfred Stevens (1823-1906) and William Degouve de Nuncques (1867-1935) were utterly fascinated by them. In the 1880s and 1890s, Whistler's "nocturne painting" was influential throughout Europe and in the United States.

Edvard Munch's Starry Night (1863-1944) belongs to this movement. In this twilit landscape, painted in 1893 (the same year as The Scream), on the banks of the fjord of Oslo, there is no artificial light, but a star, reflected in the sea as a long line. It was initially entitled The Stars, then rechristened Evening Star by Munch in 1902, thereby emphasizing the presence of the planet Venus, named after the Classical goddess of Love. It is the first work in the Frieze of Life cycle, a group of paintings about life, love and death. Munch does not seek to depict a place: instead, by wreathing the dim, mysterious shapes of the landscape in bluish mists, like Whistler, he creates a dreamlike atmosphere.

In the same period, in nearby Sweden, Eugène Jansson (1862-1915) also succeeded in conveying the poetry of night in his depictions of his favourite subject - the city of Stockholm. Jansson, who was nicknamed "the blue painter", produced an entire series of powerfully lyrical landscapes in which blue is applied in lively, overlapping strokes and highlighted with yellow-white impastos representing the lights of the modern city. Himself a pianist, Jansson was a great admirer of Chopin's music, and entitled several of his panoramic blue landscapes Nocturne.

From the moment Whistler's Nocturnes were shown in London, Paris and Brussels, they were hugely successful. A whole generation of artists including Whistler's friend and assistant Walter Greaves (1846-1930), Charles Lacoste (1870-1959), and the Belgians Alfred Stevens (1823-1906) and William Degouve de Nuncques (1867-1935) were utterly fascinated by them. In the 1880s and 1890s, Whistler's "nocturne painting" was influential throughout Europe and in the United States.

Edvard Munch's Starry Night (1863-1944) belongs to this movement. In this twilit landscape, painted in 1893 (the same year as The Scream), on the banks of the fjord of Oslo, there is no artificial light, but a star, reflected in the sea as a long line. It was initially entitled The Stars, then rechristened Evening Star by Munch in 1902, thereby emphasizing the presence of the planet Venus, named after the Classical goddess of Love. It is the first work in the Frieze of Life cycle, a group of paintings about life, love and death. Munch does not seek to depict a place: instead, by wreathing the dim, mysterious shapes of the landscape in bluish mists, like Whistler, he creates a dreamlike atmosphere.

In the same period, in nearby Sweden, Eugène Jansson (1862-1915) also succeeded in conveying the poetry of night in his depictions of his favourite subject - the city of Stockholm. Jansson, who was nicknamed "the blue painter", produced an entire series of powerfully lyrical landscapes in which blue is applied in lively, overlapping strokes and highlighted with yellow-white impastos representing the lights of the modern city. Himself a pianist, Jansson was a great admirer of Chopin's music, and entitled several of his panoramic blue landscapes Nocturne.

Eugène JANSSON (1862-1915), Nocturne, 1900, oil on canvas, 136 x 151 cm. . © Hossein Sehatlou

11 - Night and the cinematograph

Long before the cinematograph was invented in 1895, the public was able to marvel at shows in which a variety of devices of varying complexity - zograscopes, magic lanterns, dioramas, panoramas and so on - made use of the properties of light to create illusions. These devices were designed for public showings in dedicated venues, but domestic versions like the Eiffel Tower magic lantern were also made for family use.

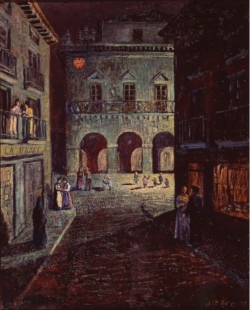

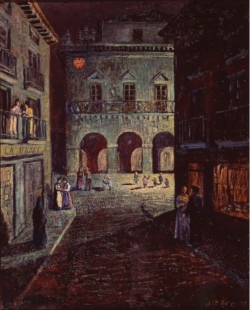

In Le Panorama du Czar (The Panorama of the Tsar in Paris, 1895), Ferdinand Loyen du Puigaudeau depicts a popular entertainment venue of this kind, where the public would come to peer through porthole-like apertures at perspective views, which were probably enlivened with day/night effects.

With perspective views, the illusion of day becoming night could be created by means of perforations, colouring and backlighting, but the cinematograph, like photography, was initially unable to take pictures of night, for technical reasons: the films used were not sensitive enough. So film directors used tricks to recreate the effect of night, shooting night scenes in natural light during the day and then tinting the film pure blue or violet. The public was quick to adapt to the colour code: soon, whenever they saw a blue-tinted scene, they instantly knew that it was taking place at night.

Georges Méliès successfully experimented with all kinds of special effects techniques. In Le Raid Paris Monte-Carlo en automobile (The Paris Monte-Carlo Rally, 1904), he created one of his finest night scenes by colouring the film with paint: the Place de l’Opéra is plunged in bluish twilight and lit by (imitation) gas-lamps, whose red flames look as if they are literally dancing. Ferdinand Zecca used the same device in Le Rêve à la Lune (Dream of the Moon, also known as The Lover of the Moon, 1905).

Of course, as a feature of the urban landscape, the lamp-post also featured in daytime scenes. Sometimes it was even given a cameo part in delightful comic scenes, triggering a collision in Les Débuts d’un chauffeur (The Inexperienced Chauffeur, 1906, directed by Georges Hatot) or being commandeered into partnering Maurice Chevalier in a zany mid-street dance number in La Valse à la mode (1908).

In Le Panorama du Czar (The Panorama of the Tsar in Paris, 1895), Ferdinand Loyen du Puigaudeau depicts a popular entertainment venue of this kind, where the public would come to peer through porthole-like apertures at perspective views, which were probably enlivened with day/night effects.

With perspective views, the illusion of day becoming night could be created by means of perforations, colouring and backlighting, but the cinematograph, like photography, was initially unable to take pictures of night, for technical reasons: the films used were not sensitive enough. So film directors used tricks to recreate the effect of night, shooting night scenes in natural light during the day and then tinting the film pure blue or violet. The public was quick to adapt to the colour code: soon, whenever they saw a blue-tinted scene, they instantly knew that it was taking place at night.

Georges Méliès successfully experimented with all kinds of special effects techniques. In Le Raid Paris Monte-Carlo en automobile (The Paris Monte-Carlo Rally, 1904), he created one of his finest night scenes by colouring the film with paint: the Place de l’Opéra is plunged in bluish twilight and lit by (imitation) gas-lamps, whose red flames look as if they are literally dancing. Ferdinand Zecca used the same device in Le Rêve à la Lune (Dream of the Moon, also known as The Lover of the Moon, 1905).

Of course, as a feature of the urban landscape, the lamp-post also featured in daytime scenes. Sometimes it was even given a cameo part in delightful comic scenes, triggering a collision in Les Débuts d’un chauffeur (The Inexperienced Chauffeur, 1906, directed by Georges Hatot) or being commandeered into partnering Maurice Chevalier in a zany mid-street dance number in La Valse à la mode (1908).

Georges MÉLIÈS (1861 -1938), Le raid Paris-Monte-Carlo en automobile , 1905, . . © Paris

12 - Photographic nocturnes

Painters and printmakers recorded the city at night long before photographers did so. Until the late nineteenth century, it was very difficult to take photographs at night: the negatives were not sensitive enough.

Day/night effects

However, from the 1850s onwards, using techniques borrowed from etching, photography managed to create the illusion of night-time using an image initially viewed under direct light, to represent daytime, then backlit to create the impression of the same scene at night. The resulting day/night effect was used for photographs of standard size, which could be viewed through optical boxes called megalethoscopes. Stereoscopic views, which were more widespread but smaller, created the same effect, with the addition of contours. As for the previous views, several layers of translucent paper were superimposed on the photographs, but in addition, these were enhanced by adding areas of colour, shadows and painted designs drawn or cut out of the extra thickness of paper, on the back to allow the viewer to marvel at fireworks or illuminations in a street or square or on a monument.

Night-time photography

A few pioneers in Europe and the USA rose to the challenge of night-time photography in the mid-1880s. They surmounted the technical problems by using very long exposure times (from several minutes to half an hour). The French painter Gabriel Loppé, who was a keen photographer, took pictures of the Eiffel Tower being built, including some night-time photographs. In 1896, the Englishman Paul Martin won a prize for his night-time views of London. Léon Gimpel, another pioneer of night-time photography, had some success before 1900. He then took photographs of the lights in Marseille and Paris, some of which were immediately published by the newspaper L’Illustration, especially at international exhibitions and World's Fairs, or trade fairs such as the Paris Motor Show.

Night-time photography was subsequently facilitated by technical advances in the production of negatives shortly before World War 1.

Colour

At the end of the 1900s, Léon Gimpel took night-time photographs using autochrome, the first commercial colour photography technique, invented in 1904 by the Lumière brothers.

Day/night effects

However, from the 1850s onwards, using techniques borrowed from etching, photography managed to create the illusion of night-time using an image initially viewed under direct light, to represent daytime, then backlit to create the impression of the same scene at night. The resulting day/night effect was used for photographs of standard size, which could be viewed through optical boxes called megalethoscopes. Stereoscopic views, which were more widespread but smaller, created the same effect, with the addition of contours. As for the previous views, several layers of translucent paper were superimposed on the photographs, but in addition, these were enhanced by adding areas of colour, shadows and painted designs drawn or cut out of the extra thickness of paper, on the back to allow the viewer to marvel at fireworks or illuminations in a street or square or on a monument.

Night-time photography

A few pioneers in Europe and the USA rose to the challenge of night-time photography in the mid-1880s. They surmounted the technical problems by using very long exposure times (from several minutes to half an hour). The French painter Gabriel Loppé, who was a keen photographer, took pictures of the Eiffel Tower being built, including some night-time photographs. In 1896, the Englishman Paul Martin won a prize for his night-time views of London. Léon Gimpel, another pioneer of night-time photography, had some success before 1900. He then took photographs of the lights in Marseille and Paris, some of which were immediately published by the newspaper L’Illustration, especially at international exhibitions and World's Fairs, or trade fairs such as the Paris Motor Show.

Night-time photography was subsequently facilitated by technical advances in the production of negatives shortly before World War 1.

Colour

At the end of the 1900s, Léon Gimpel took night-time photographs using autochrome, the first commercial colour photography technique, invented in 1904 by the Lumière brothers.

Léon Gimpel, Salon d’Automne, novembre 1903, , 9 x 12 cm. . © Collection Société française de photographie

13 - Staring head-on at light

In Paris, the advent of the twentieth century was greeted with the 1900 World's Fair, at which electricity was the star. In addition to lighting, it revolutionized transport (with trams, underground trains and so on), communications (with innovations such as the telephone and the electric telegraph), science, industry and so on, permanently transforming the modern urban setting.

The first lit-up advertising signs appeared in London and New York in 1899. Ten years later, Georges Claude, a French physicist, perfected the first lighting tubes. Night was now garbed in colour, "letters of fire" adorned the facades of buildings, and winking and flashing lights turned the city into a show that never stopped, in a constant state of restless tension.

Kees van Dongen's Le Carrousel (Roundabout, 1901) sweeps us up into a dizzying whirl of fast-moving shapes and dazzling lights. In 1905-1906, opting for a format generally used only for landscapes, he painted a picture of the interior of the dance-hall of the Moulin de la Galette, showing the customers making merry in "a bacchanalia of light, under suns burning with colours." In around 1950-1960, he cut the picture up into six fragments. By isolating the chandelier that lit the dance-hall, he transformed it into a contemporary heavenly body, emphasizing the radiant energy of electric light even more effectively.

Avant-garde artists such as the Futurists, the Rayonists and the Orphists saw electricity as the embodiment of modernity. They were fascinated with optical phenomena and what happens when light propagates in space, and invented a new visual language to explore its effects.

Getting as close as she can to the Lampe électrique (The Electric Lamp, 1913), Natalia Goncharova ceases to pay attention to the objects it illuminates: instead, she attempts to reproduce the sensation of being blinded by a light-bulb when you look at it head-on.

Tommaso Marinetti, who theorized Futurism, was equally fascinated with modern lighting, of which he wrote, "Every night, I pray to my electric light-bulb, because it whirs with a furious inner velocity."

Sonia Delaunay took the experiment further. Abandoning all figurative reference to the light-source, she transposes the experience of being dazzled into the motif of the disc fragmented into concentric rings in all colours of the prism. The discs express the energy of matter and an infinite perceived space.

In contrast to this exalted vision, other artists offer more disturbing representations of the city at night. The frenetic "City of Light", cluttered with posters and lit-up advertising signs, is like a many-faceted kaleidoscope. Immersed in the Montmartre night, Auguste Chabaud juxtaposes the signs of this modernity in a kind of visual collage, proposing a telescoped vision of the scene, devoid of all semblance of unity.

Progress, embodied by the increasing presence of lighting and by speed, takes on a threatening quality. Half fascinated, half repelled, Jacob Steinhardt, like the Expressionists, delivers a harrowing image of street life in a great metropolis, in which no one escapes the white light of the electric pylons - neither the ghostly crowd walking around beneath them, nor the people who occupy the buildings, whom we glimpse through the windows, with their almost corpse-like appearance.

This was the eve of the First World War, and Guillaume Apollinaire's "Soirs de Paris ivres du gin / flambant de l’électricité" ("Paris evenings drunk on gin/flaming with electricity", La Chanson du mal-aimé) seem to echo Marinetti's exhortation "Let us kill moonlight!", which furnished the second Futurist manifesto with its provocative title.

The first lit-up advertising signs appeared in London and New York in 1899. Ten years later, Georges Claude, a French physicist, perfected the first lighting tubes. Night was now garbed in colour, "letters of fire" adorned the facades of buildings, and winking and flashing lights turned the city into a show that never stopped, in a constant state of restless tension.

Kees van Dongen's Le Carrousel (Roundabout, 1901) sweeps us up into a dizzying whirl of fast-moving shapes and dazzling lights. In 1905-1906, opting for a format generally used only for landscapes, he painted a picture of the interior of the dance-hall of the Moulin de la Galette, showing the customers making merry in "a bacchanalia of light, under suns burning with colours." In around 1950-1960, he cut the picture up into six fragments. By isolating the chandelier that lit the dance-hall, he transformed it into a contemporary heavenly body, emphasizing the radiant energy of electric light even more effectively.

Avant-garde artists such as the Futurists, the Rayonists and the Orphists saw electricity as the embodiment of modernity. They were fascinated with optical phenomena and what happens when light propagates in space, and invented a new visual language to explore its effects.

Getting as close as she can to the Lampe électrique (The Electric Lamp, 1913), Natalia Goncharova ceases to pay attention to the objects it illuminates: instead, she attempts to reproduce the sensation of being blinded by a light-bulb when you look at it head-on.

Tommaso Marinetti, who theorized Futurism, was equally fascinated with modern lighting, of which he wrote, "Every night, I pray to my electric light-bulb, because it whirs with a furious inner velocity."

Sonia Delaunay took the experiment further. Abandoning all figurative reference to the light-source, she transposes the experience of being dazzled into the motif of the disc fragmented into concentric rings in all colours of the prism. The discs express the energy of matter and an infinite perceived space.

In contrast to this exalted vision, other artists offer more disturbing representations of the city at night. The frenetic "City of Light", cluttered with posters and lit-up advertising signs, is like a many-faceted kaleidoscope. Immersed in the Montmartre night, Auguste Chabaud juxtaposes the signs of this modernity in a kind of visual collage, proposing a telescoped vision of the scene, devoid of all semblance of unity.

Progress, embodied by the increasing presence of lighting and by speed, takes on a threatening quality. Half fascinated, half repelled, Jacob Steinhardt, like the Expressionists, delivers a harrowing image of street life in a great metropolis, in which no one escapes the white light of the electric pylons - neither the ghostly crowd walking around beneath them, nor the people who occupy the buildings, whom we glimpse through the windows, with their almost corpse-like appearance.

This was the eve of the First World War, and Guillaume Apollinaire's "Soirs de Paris ivres du gin / flambant de l’électricité" ("Paris evenings drunk on gin/flaming with electricity", La Chanson du mal-aimé) seem to echo Marinetti's exhortation "Let us kill moonlight!", which furnished the second Futurist manifesto with its provocative title.

Sonia Delaunay (Stern Terk Sarah Sophie, Prismes électriques, 1914, oil on canvas, 250 x 250 cm. . © Pracusa S.A.