History

The Musée d’art moderne André Malraux opened in 1845. It is Le Havre’s first museum and belongs to the second generation of museums established in France in the 19th century.

- Photographer Pierre Joly, on the roof of the Musée-maison de la culture, 1961. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

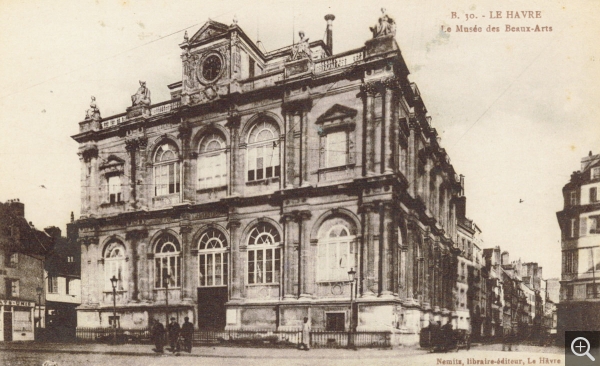

- Le musée des beaux-arts du Havre, ca. 1930, postcard. © Le Havre, musées historiques

- Le musée des beaux-arts du Havre, paintings room, postcard. © Le Havre, musées historiques

- Beginning construction of the Musée-maison de la culture in Le Havre. Crane track, construction of the ground floor, 1959. © Le Havre, archives municipales

- Bird’s-eye view of the Musée-maison de la culture, postcard. © Le Havre, archives municipales

- Construction site, Musée-maison de la culture. Construction of the louvre and metal frame of the north and east facades, 1960. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Interstitial space between the louvre and the reinforced glass roof, 1960. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Construction site, Musée-maison de la culture, Le Havre. Interior view over the west facade, formwork of The Signal, 1960. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- From the museum interior: perspective view over the completed The Signal and placement of the door designed by Jean Prouvé, 1960. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Façade over the Musée-maison de la culture. © MuMa Le Havre

- On the mezzanine, perspective view over the collections. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Bar-club of the Musée-maison de la culture, Le Havre with Reynold Arnould’s tapestry The Wave. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Inaugural exhibition "École de Paris. Art décoratif". Atrium, 1961. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- The atrium as concert hall, June 24, 1961. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Pierre-Michel Leconte conducting André Jolivet’s Rhapsody for Seven. Inauguration concert. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Inaugural exhibition "École de Paris. Art décoratif". © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Musée-maison de la culture, Le Havre. View from the corner of rue Benjamin-Normand, 1961. © MuMa Le Havre

- The Angel, sculpture of François Stahly. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Interior view over the large aluminum door designed by Jean Prouvé, 1961. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- André Malraux in front of The Signal, June 24, 1961, during the inauguration of the Musée-maison de la culture, Le Havre. © Centre Pompidou, bibliothèque Kandinsky, fonds Cardot-Joly / Pierre Joly - Véra Cardot

- Interior view, June 1965. Photothèque de la DICOM © MEDDE / MLETR

- Bird’s-eye view of the Musée-maison de la culture, June 1965. Photothèque de la DICOM © MEDDE / MLETR

1845–1944: The Le Havre Museum of Fine Arts

Le Havre's first Musée des Beaux-Arts was built in 1845 by architect Charles Fortuné Brunet-Debaines on the former site of the Logis du Roy (governor's residence). It was at the very same location—on the corner of the busy, shop-filled rue de Paris and quai de Southampton—that the city's first public art exhibitions were held in 1839.

Originally, the museum's collections were extremely varied, covering the decorative arts, painting, sculpture and natural history. The museum was also home to the city library. Gradually, the building was taken over for other uses. In 1881, the museum was moved to the place du Vieux-Marché, and in 1904 the library was relocated to the Boys' lycée. In 1920, a sculpture museum opened in the Graville priory, Le Havre's oldest monument. In the meantime, the museum had sharpened its focus on the fine arts and, in 1900, rolled out a bold new acquisition policy focusing on contemporary art. The museum's collection of works grew, offering a fine overview of the history of painting in Europe.

In September 1944, the museum was destroyed by bombings. The sculpture collection, which remained at the museum throughout the war, was almost entirely lost. Only the paintings—some 1,500 works moved off site for safekeeping during the war—survived.

Originally, the museum's collections were extremely varied, covering the decorative arts, painting, sculpture and natural history. The museum was also home to the city library. Gradually, the building was taken over for other uses. In 1881, the museum was moved to the place du Vieux-Marché, and in 1904 the library was relocated to the Boys' lycée. In 1920, a sculpture museum opened in the Graville priory, Le Havre's oldest monument. In the meantime, the museum had sharpened its focus on the fine arts and, in 1900, rolled out a bold new acquisition policy focusing on contemporary art. The museum's collection of works grew, offering a fine overview of the history of painting in Europe.

In September 1944, the museum was destroyed by bombings. The sculpture collection, which remained at the museum throughout the war, was almost entirely lost. Only the paintings—some 1,500 works moved off site for safekeeping during the war—survived.

1952–1961: Reconstruction

In 1951, the City of Le Havre decided to build a new museum.

But the project stalled due to difficulty reaching decisions as to the museum's official status and location. Georges Salles, then Director of Musées de France, and Le Havre-born artist Reynold Arnould, who had been appointed Curator of the city's museums, spearheaded efforts to get things moving again, and the project started in 1952.

Not only did the two men want to replace the building destroyed in the war with a new building to house the city's collections; they also wanted to break with tradition and rethink the very role of the museum. Their vision of the museum was a place where lectures, film screenings, and concerts could be held—creating the need for a variety of new spaces, from exhibition halls, art studios, and storage for works not on display to cafeterias, photographic archives, and book and record libraries.

Well before museums were viewed as full-fledged cultural centres, Le Havre's new museum would be tasked with getting the general public interested in the arts and contributing to arts education initiatives. All that was needed for the bold new museum project—more modern than any other in Europe—was an architect. And Guy Lagneau, who had broken rank with Auguste Perret's Le Havre post-war reconstruction studio, fit the bill perfectly. Lagneau and his partners Raymond Audigier, Michel Weill and Jean Dimitrijevic sought harmony with the maritime environment, inventing a flexible, transparent, modular building with mobile partition walls.

The glass, steel and aluminum cube let in abundant natural light from all sides—even the roof—creating a constant conversation between the works on display and the landscapes and light that inspired their creators. Poised at the entrance to the port of Le Havre much like a figurehead, MuMa, France's first museum built after the war, and The Signal, Henri-Georges Adam's monumental sculpture, stand together as a manifesto for modern, minimalist architecture.

But the project stalled due to difficulty reaching decisions as to the museum's official status and location. Georges Salles, then Director of Musées de France, and Le Havre-born artist Reynold Arnould, who had been appointed Curator of the city's museums, spearheaded efforts to get things moving again, and the project started in 1952.

Not only did the two men want to replace the building destroyed in the war with a new building to house the city's collections; they also wanted to break with tradition and rethink the very role of the museum. Their vision of the museum was a place where lectures, film screenings, and concerts could be held—creating the need for a variety of new spaces, from exhibition halls, art studios, and storage for works not on display to cafeterias, photographic archives, and book and record libraries.

Well before museums were viewed as full-fledged cultural centres, Le Havre's new museum would be tasked with getting the general public interested in the arts and contributing to arts education initiatives. All that was needed for the bold new museum project—more modern than any other in Europe—was an architect. And Guy Lagneau, who had broken rank with Auguste Perret's Le Havre post-war reconstruction studio, fit the bill perfectly. Lagneau and his partners Raymond Audigier, Michel Weill and Jean Dimitrijevic sought harmony with the maritime environment, inventing a flexible, transparent, modular building with mobile partition walls.

The glass, steel and aluminum cube let in abundant natural light from all sides—even the roof—creating a constant conversation between the works on display and the landscapes and light that inspired their creators. Poised at the entrance to the port of Le Havre much like a figurehead, MuMa, France's first museum built after the war, and The Signal, Henri-Georges Adam's monumental sculpture, stand together as a manifesto for modern, minimalist architecture.

1961–1967: The museum as cultural centre

André Malraux's inaugural speech on June 24, 1961 made Le Havre's new museum of modern art a symbol of efforts to promote culture and the arts: "You won't find another museum quite like this one anywhere in the world – not in Brazil, not in Russia, not even in the United States. People of Le Havre, one day you will proudly be able to say that it all started right here."

In 1961, the museum stood as an outpost of the city of Le Havre. It was the first thing transatlantic travellers arriving at port saw when they arrived—a beacon sending a clear signal of France's avant-garde approach to culture and the arts. And the museum that was designed as a full-fledged cultural centre—a place for making and interacting with art as much as contemplating it—hosted a range of activities, from exhibitions and concerts to lectures and performances.

The museum paved the way for France's burgeoning network of cultural centres, instruments of social action designed to provide opportunities for public interaction with the arts and to allow the public to rediscover works of art. Le Havre's museum was a home to art in all of its forms, giving the public access to collections built up over more than a century and providing a particularly generous offering of cultural activities like temporary exhibitions, film screenings, lectures, concerts, and art and record libraries.

However, the museum's multitude of uses rapidly became unmanageable, especially from a security standpoint. In 1967, the cultural centre was transferred to the Théâtre de l'Hôtel de Ville, and the museum once again became just that—a museum.

In 1961, the museum stood as an outpost of the city of Le Havre. It was the first thing transatlantic travellers arriving at port saw when they arrived—a beacon sending a clear signal of France's avant-garde approach to culture and the arts. And the museum that was designed as a full-fledged cultural centre—a place for making and interacting with art as much as contemplating it—hosted a range of activities, from exhibitions and concerts to lectures and performances.

The museum paved the way for France's burgeoning network of cultural centres, instruments of social action designed to provide opportunities for public interaction with the arts and to allow the public to rediscover works of art. Le Havre's museum was a home to art in all of its forms, giving the public access to collections built up over more than a century and providing a particularly generous offering of cultural activities like temporary exhibitions, film screenings, lectures, concerts, and art and record libraries.

However, the museum's multitude of uses rapidly became unmanageable, especially from a security standpoint. In 1967, the cultural centre was transferred to the Théâtre de l'Hôtel de Ville, and the museum once again became just that—a museum.

1995–1999: Restructuring

Over the years, the museum's maritime environment took its toll on the building, and the permanent collection was outgrowing the space available in the exhibit halls.

In 1993, the City of Le Havre decided that piecemeal remodelling, which risked diluting the overall architectural quality of the building, was not the answer. An international architecture competition was held, and architects were asked to submit plans for a complete overhaul of the museum. Emmanuelle and Laurent Beaudouin won the competition, and, from 1995 to 1999, restructured the building from top to bottom, enhancing the original architecture and landscaping design.

In 1993, the City of Le Havre decided that piecemeal remodelling, which risked diluting the overall architectural quality of the building, was not the answer. An international architecture competition was held, and architects were asked to submit plans for a complete overhaul of the museum. Emmanuelle and Laurent Beaudouin won the competition, and, from 1995 to 1999, restructured the building from top to bottom, enhancing the original architecture and landscaping design.

2011: Museum turns 50 and gets a new name

The restructured museum was renamed the Musée Malraux in 1999. It changed names once again in 2011—the year of its 50th anniversary—to become the Musée d'art moderne André Malraux—or MuMa ("Mu" for museum and "Ma" for Malraux) for short. The rationale behind this new name change was twofold: first, to give the museum a name that clearly reflected the type of works in its collections and, second, to highlight the museum's contemporary approach to programming.

For the 50th anniversary festivities held from October 15, 2011 to January 29, 2012, the Musée d'art moderne André Malraux stole a line from Arthur Rimbaud: "When you are 50, you aren't really serious." The anniversary was the occasion to reaffirm the museum's image as a modular, constantly evolving centre for culture and the arts—the very concept behind its creation in 1961. The festivities, open to the general public, included a new exhibition each week (12 in all), as well as lectures and performances. The goal was to rekindle the bold, experimental spirit of the museum whose first director, Reynold Arnould, conceived of the museum as "the agora of our century, the place where necessary conversations happen."

For the 50th anniversary festivities held from October 15, 2011 to January 29, 2012, the Musée d'art moderne André Malraux stole a line from Arthur Rimbaud: "When you are 50, you aren't really serious." The anniversary was the occasion to reaffirm the museum's image as a modular, constantly evolving centre for culture and the arts—the very concept behind its creation in 1961. The festivities, open to the general public, included a new exhibition each week (12 in all), as well as lectures and performances. The goal was to rekindle the bold, experimental spirit of the museum whose first director, Reynold Arnould, conceived of the museum as "the agora of our century, the place where necessary conversations happen."