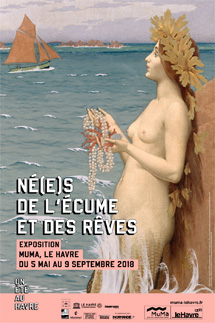

Ocean Imaginings

from May 05 to September 09, 2018

MuMa's major 2018 spring and summer exhibition "Ocean Imaginings" explores imaginative interpretations of the sea, the ocean and the undersea world in art works from the second half of the nineteenth century and the twentieth century, a period in which attitudes to the marine world were decisively transformed by the new discipline of oceanography.

Curated by Annette Haudiquet, Director of MuMa, Denis-Michel Boëll, General Curator of Heritage, and Marc Donnadieu, Chief Curator of the Musée de l’Elysée (Lausanne), "Ocean Imaginings" juxtaposes works that have never previously been seen together from numerous public and private collections based in France and abroad, including the Centre Pompidou (which has loaned 50 works for the exhibition), the Musée d’Orsay, the Petit Palais, the Musée Rodin, the Cinémathèque Française, the Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, the Musée de l’Ecole de Nancy, Indianapolis Museum of Art and the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek in Copenhagen.

The Century of Science

The nineteenth century was marked by ground-breaking scientific advances that considerably altered people's attitudes to their environment.

In 1859, Darwin published his book On the Origin of Species setting out the theory of evolution. That same year, the first underwater telephone cable was laid between Europe and America, and France's first laboratory of marine zoology and physiology was set up in Concarneau, in Brittany. It was soon followed by a dozen maritime research stations on the French coasts. For artists like Jean-Francis Auburtin and Mathurin Méheut, they were ideal places to observe marine life. Meanwhile, from 1898 onwards, Louis Boutan was experimenting with underwater photography at Concarneau, the Swiss artist Arnold Böcklin was becoming fascinated by the research being carried out at a marine zoology station founded in Naples in 1872.

Three seminal works of literature focusing on the ocean had been published in the 1860s, before painting took up the theme: Jules Michelet's La Mer (The Sea, 1861), Victor Hugo's Les Travailleurs de la mer (Toilers of the Sea, 1866), and the Comte de Lautréamont's Les Chants de Maldoror (The Songs of Maldoror, 1868-1869). Gustave Doré provided illustrations for an 1867 edition of Les Travailleurs de la mer, ten years before illustrating The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, by Samuel Taylor Coleridge. In 1869, Jules Verne published his adventure story Vingt mille lieues sous les mers (Twenty Thousand Leagues under the Sea), a modern take on the legend of Atlantis. The figure of Captain Nemo and his submarine, the Nautilus, owed much of their popularity to the illustrations of Alphonse de Neuville and Édouard Riou.

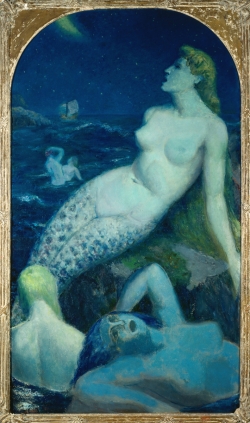

Paul-Alex DESCHMACKER (1889-1973), La grande sirène bleue, vers 1937, oil on canvas, 1.21 m x 2.11 m. . © Musée La Piscine, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais/Arnaud Loubry

At the Paris Salon of 1863, raditional representations of the birth of Venus by Cabanel, Baudry and Amaury-Duval still dominated the art scene. But very soon, under the influence of the new scientific discoveries about the marine world, artists began to drift away from classical mythology and the Greek and Latin literary canon that had furnished so many stories and characters connected with the sea (Odysseus and the Sirens, Venus, Andromeda, Medusa, Ondine, and so on) and to explore new, unfamiliar narratives, shapes and motifs. Gustave Moreau and Odilon Redon offer consummate illustrations of this shift. Exhibition galleries began to be filled with a plethora of marine phantasmagoria - ambivalent hybrid monsters, half woman, half fish or half woman, half seahorse. As depicted by Auguste Rodin, Arnold Böcklin and English painters of the Victorian era, the Sirens no longer had wings. Transformed into mermaids, they lured poets and fishermen to a watery death.

Henri GERVEX (1852-1929), Naissance de Vénus, 1907, oil on canvas, 160.5 x 200 cm. . © Petit Palais / Roger-Viollet

Modern and Surrealist Visions

In the period between the wars, modern artists saw the undersea world as a lost Eden or a magic mirror held up to the world on land. The pen of André Breton, the scissors of Max Ernst and the paintbrush of Hans Reichel jumbled distances, boundaries and horizons beyond repair. The Surrealists found ample evidence in Jean Painlevé's popular science films that reality was just as capable of sparking imaginative visions as the human mind, if not more so. This was the "circumstantial magic" alluded to in André Breton's rallying cry. Seaweed, plankton, corals, octopuses, jellyfish, seahorses and starfish are frequently to be found in the photographs of Laure Albin-Guillot, Brassaï, Man Ray and André Steiner.

In the visions of Jacques-André Boiffard, Heinz Hajek-Halke and Roger Parry, these marine apparitions sometimes conjure up the very stuff of dreams, functioning as André Breton's "fixed-explosives". Nurtured by the chimeric imaginings of Victor Hugo, Lautréamont, Joris-Karl Huysmans and Alfred Jarry, and by the rise of totalitarian regimes, new monsters also made their appearance, as in the experimental creations of Lucien Lorelle, Raoul Ubac and Wols, and later Simon Hantaï and Judit Reigl. The trope of the aquarium was transformed from a scale model of the ocean into a world of conjuror's illusions or music-hall turns: natural marvels were replaced by a new kind of show, imbued with Breton's concept of veiled-erotic convulsive beauty.

The Future of the Oceans

Artists take part in new-style scientific expeditions

Today, the oceans have lost their terrors. For centuries, human beings had a primeval fear of the sea: now we are afraid not of, but for the marine biotope. Contemporary art reflects climate change, overexploitation of natural resources and marine pollution.

Elsa GUILLAUME (1989), 2012, ceramic. . © Photo Elsa Guillaume

Here, 28-year-old visual artist Elsa Guillaume is exhibiting Spacesuit, a fragmented ceramic and enamel diver's helmet suspended in mid-air, made in São Paulo in 2012, and two pieces especially created for the exhibition - a 14-metre drawing of marine riders exploring the sea-bed, done in situ, and in front of it, forming a counterpoint, an installation consisting of three large porcelain spider crabs. Meanwhile, the many-faceted Nicolas Floc’h, who uses painting, sculpture and photography to explore aquatic environments, landscapes and transformations of the sea, is showing four large-format prints of his photographs of the sea-bed at Ouessant, in Brittany and Kuroshio, in Japan, taken on an expedition ith the schooner Tara in 2017. Floc'h invites us to share his observation of the effects of global warming and ocean acidification in these two series documenting rapidly changing undersea landscapes.

A museum that looks seaward

MuMa - the André Malraux Museum of Modern Art - was the first museum to be rebuilt in France following World War 2. Opened in 1961 by André Malraux, its high modernist glass-and-steel building is superbly located in Auguste Perret's reconstructed city centre, overlooking the harbour entrance. It offers an outstanding view of the seascape and of the Seine estuary that has appealed to so many artists.

The proximity of the sea and the nature of the museum's collections, which chiefly revolve around French painting from the late nineteenth century and the early decades of the twentieth century, substantially determine the choice of exhibition themes. "Ocean Imaginings" follows on from exhibitions on the theme of waves ("Vagues. Autour des paysages de mer de Gustave Courbet" in 2004) or ports ("Sur les quais. Ports, docks et dockers, de Boudin à Marquet" in 2008, "Signac et les ports de France" in 2010 and "Pissarro et les ports. Rouen, Dieppe, Le Havre" in 2013).

Exhibition curators:

Annette Haudiquet, Chief Curator, MuMa

Denis-Michel Boëll, General Curator of Heritage

Marc Donnadieu, Chief Curator of the Musée de l’Elysée (Lausanne)

The exhibition "Ocean Imaginings" is part of the programme of cultural events entitled "A Summer in Le Havre", initially rolled out in 2017 to celebrate the 500-year anniversary of the founding of the city and harbour of Le Havre.

"A Summer in Le Havre" is devised by artistic director Jean Blaise and coordinated by the GIP (public interest group) "Le Havre 2017" made up of the City of Le Havre, the Communauté de l’Agglomération Havraise (Greater Le Havre Conurbation), the Grand Port Maritime du Havre (Le Havre Port Authority), the Seine Estuary Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Department of Seine-Maritime and the University of Le Havre.

Documents téléchargeables