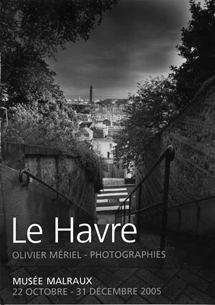

Olivier Mériel. Le Havre, photographies

from October 22 to December 31, 2005

Olivier Mériel has a deep connection with his native Normandy and has been photographing its shores, coastline and hinterland for almost thirty years. In 2003, he began a series of photographs of Le Havre. Two years later, he had produced some fifty photographs presenting a sensitive and highly personal portrait of the city.

The artist covered Le Havre from north to south, east to west. He combed the city from the upper town to the industrial Eure district, walking through Les Neiges and Graville, along the docks and down to the sea. He surveyed the area slowly, with no preconceived plan, guide or map, simply going where his feet took him.

Olivier Mériel works with equipment as old as the history of photography itself: the view camera (one 20x25 and one 30x40). Although it can be cumbersome to use, he feels the results are incomparable for the view camera can produce close-ups and long-shots in the same image and with the same sharpness. The artist explains this is something our eye cannot perceive in reality, but that we can find in the compositions of the Dutch masters where "the foreground is as if captured by a wide-angle while the background seems to have been shot with a telephoto lens, which is impossible!"

Using the view camera requires a special notion of time and a demanding routine: you have to transport the camera, set it up, disappear under the dark cloth, focus the image, wait for suitable light, trigger the shutter. Preparing a shot can take several hours. That is why you find very few people in Olivier Mériel's photographs... the long exposures have disembodied the many silhouettes that nevertheless passed through the lens.

The sweeping views over the bay of Le Havre, the stairs to the upper town, the avenues of the rebuilt city centre, the basins and the slipways, the inside of a docker café and the Museum of Natural History's reserves all paint a poetic portrait of the city, in a slowed, almost stretched out, temporality that transforms reality.