Cordier, The Nubians

Charles-Henri-Joseph CORDIER (1827-1905)

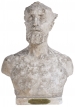

Nubian Man

1848

bronze

h. : 85 cm

© MuMa Le Havre / Charles Maslard

Nubian Man

1848

bronze

h. : 85 cm

© MuMa Le Havre / Charles Maslard

Charles-Henri-Joseph CORDIER (1827-1905)

Nubian Woman

1851

bronze

h. : 82 cm

© MuMa Le Havre / Charles Maslard

Nubian Woman

1851

bronze

h. : 82 cm

© MuMa Le Havre / Charles Maslard

A student of François Rude, Charles Cordier (Cambrai, 1827–Algiers, 1905) occupies a special place in French sculpture of the late 19th century. His 1847 encounter with Seïd Enkess, a former black slave turned model, determined the course of his career and marked the beginnings of his great plan to represent human diversity. His "anthropological and ethnographical gallery" project was fully in line with the emerging ethnographic approach and shared the objective of the abolitionist and protection of freedoms movements of the mid-19th century. Exhibited for the first time at the Salon of 1848—the year the Second Republic officially abolished slavery—under the title Saïd Abdallah, of the Mayac tribe, Darfour kingdom, the bust did not go unnoticed. In 1851, the State commissioned a copy for the new anthropology gallery at the Paris Museum of Natural History. Queen Victoria also bought a copy, as well as a cast of Nubian Woman, which were displayed side by side at the London World's Fair. By 1858, copies of these two works had entered the collections of the Le Havre museum, following an exhibition held by the Société des Amis des Arts.

While these first anthropological busts, like those of the Chinese, portrayed men and women encountered in Paris, in 1856 Cordier began going to his models as he travelled in Algeria, Italy, Greece and Egypt. The "ethnographical gallery" he assembled was thus not limited to non-Western types; there were also Young Woman of Trastevere and Young Woman of the Morvan, Gaulish Type, as well as Type of a woman from the Paris area. Refusing to make moulds from live models, which he felt "weakened the flesh" and "dulled physiognomic features", he aimed to express the truth and beauty of the "types" encountered during his travels by means of observation and synthesis. A pioneer, he also explored the possibilities of polychrome using patinas and recently rediscovered materials like Algerian onyx marble, which allowed for new and often sumptuous finishes of costumes and skin tones.

A profoundly generous man, Cordier dedicated his art to promoting respect for others in their uniqueness. In 1862, he declared before the French Society of Anthropology : "Because beauty is not the province of privileged race, I give to the world of art the idea of the universality of beauty. Every race has its beauty, which differs from that of other races. The most beautiful negro is not the one who looks most like us." Such innovative language for 1862 has special resonance in Le Havre, from where, in the 17th century alone, nearly one hundred thousand blacks were sent to slavery. With the acquisition of these two busts just ten years after the abolition of slavery, the city deliberately confronted its past, while paying homage to the tragic fate of thousands of men and women.

While these first anthropological busts, like those of the Chinese, portrayed men and women encountered in Paris, in 1856 Cordier began going to his models as he travelled in Algeria, Italy, Greece and Egypt. The "ethnographical gallery" he assembled was thus not limited to non-Western types; there were also Young Woman of Trastevere and Young Woman of the Morvan, Gaulish Type, as well as Type of a woman from the Paris area. Refusing to make moulds from live models, which he felt "weakened the flesh" and "dulled physiognomic features", he aimed to express the truth and beauty of the "types" encountered during his travels by means of observation and synthesis. A pioneer, he also explored the possibilities of polychrome using patinas and recently rediscovered materials like Algerian onyx marble, which allowed for new and often sumptuous finishes of costumes and skin tones.

A profoundly generous man, Cordier dedicated his art to promoting respect for others in their uniqueness. In 1862, he declared before the French Society of Anthropology : "Because beauty is not the province of privileged race, I give to the world of art the idea of the universality of beauty. Every race has its beauty, which differs from that of other races. The most beautiful negro is not the one who looks most like us." Such innovative language for 1862 has special resonance in Le Havre, from where, in the 17th century alone, nearly one hundred thousand blacks were sent to slavery. With the acquisition of these two busts just ten years after the abolition of slavery, the city deliberately confronted its past, while paying homage to the tragic fate of thousands of men and women.